General |

Writ of Summons: How to Respond?

A court case begins when the plaintiff files a formal complaint against you (hereby also known as the defendant) with the Court and serves you a Writ of Summons (see an example here) – a legal document addressed to the defendant to commence legal proceedings.

Civil actions involving substantial disputes of fact are commenced by way of a writ. These include, but are not limited to:

- Contract actions, e.g., claim for damages resulting from a breach of contractual terms and obligations, etc;

- Tort actions, e.g., claim for damages with respect to property damage resulting from road accidents and negligence, Claim for damages resulting from fraud and defamation, etc;

- Personal Injury actions, eg, claim for damages in respect of personal injury and/or death resulting from road and industrial accidents or negligence, etc;

- Intellectual property actions e.g. for damages resulting from infringement of copyright, trademarks, or patents;

Service of Writ of Summons

Prior to the Writ of Summons being served on the defendant, it must be filed and processed by the court for issuance.

The Rules of Court require the plaintiff to serve the Writ of Summons on the defendant or his / her lawyer within a stipulated time.

If the plaintiff fails to serve the writ within the stipulated time, the writ will become invalid and will have to be renewed by the way of a court summons.

For service in Singapore: the plaintiff has 6 months to serve the writ. The only exception is admiralty proceedings where the writ is valid for 12 months.

For service outside of Singapore: The time limit is 12 months.

A plaintiff can serve a writ via personal service or substituted service:

a) Personal Service

Personal service refers to the direct service of a writ to the defendant.

Service of the Writ for Individuals: A copy of the writ must be delivered to the defendant by hand. Law firms in Singapore may also send a letter to the defendant requesting the defendant to personally collect the Writ of Summons at the lawyer’s office.

Serving the Writ on a Company: A copy of the writ must be delivered to an “agent” of the company, who can be a director or an officer who accepts the service on behalf of the company. Alternatively, the Writ can be sent by registered mail to the company’s registered office.

b) Substituted Service

Substituted service refers to the indirect service of a writ to the defendant, which includes:

- By post to the individual defendant. The plaintiff should provide evidence that the defendant is resident or can be located at the property.

- By email to a registered and active email address of the defendant. The plaintiff must show that the electronic mail account to which the document will be sent, belongs to the defendant to be served.

- Dropping it off at the defendant’s workplace.

- Giving it to a friend or family member of the defendant.

Before the Court grants permission for substituted service, it must be satisfied that personal service is impractical, and at least two reasonable attempts have been made to serve the writ.

In an application for substituted service, the applicant shall demonstrate by way of an affidavit to the Court the reasons why he or she believes that the attempts at service made were reasonable.

What if you are Outside of Singapore?

If a plaintiff wants to sue you when you are not in Singapore presently, it is possible for him to approach the court for permission to serve the Writ of Summons.

The court has the power, under the Rules of Court, to grant permission for the Writ of Summons to be served outside of Singapore in certain circumstances, for example:

- To enforce a contract that was signed in Singapore;

- Where the defendant runs a business or has property in Singapore;

- To claim for the administration of the estate of a person domiciled in Singapore at the time of his death;

- The act or omission that gave rise to a tort action occurred in Singapore.

What should you do if you receive a Writ of Summons?

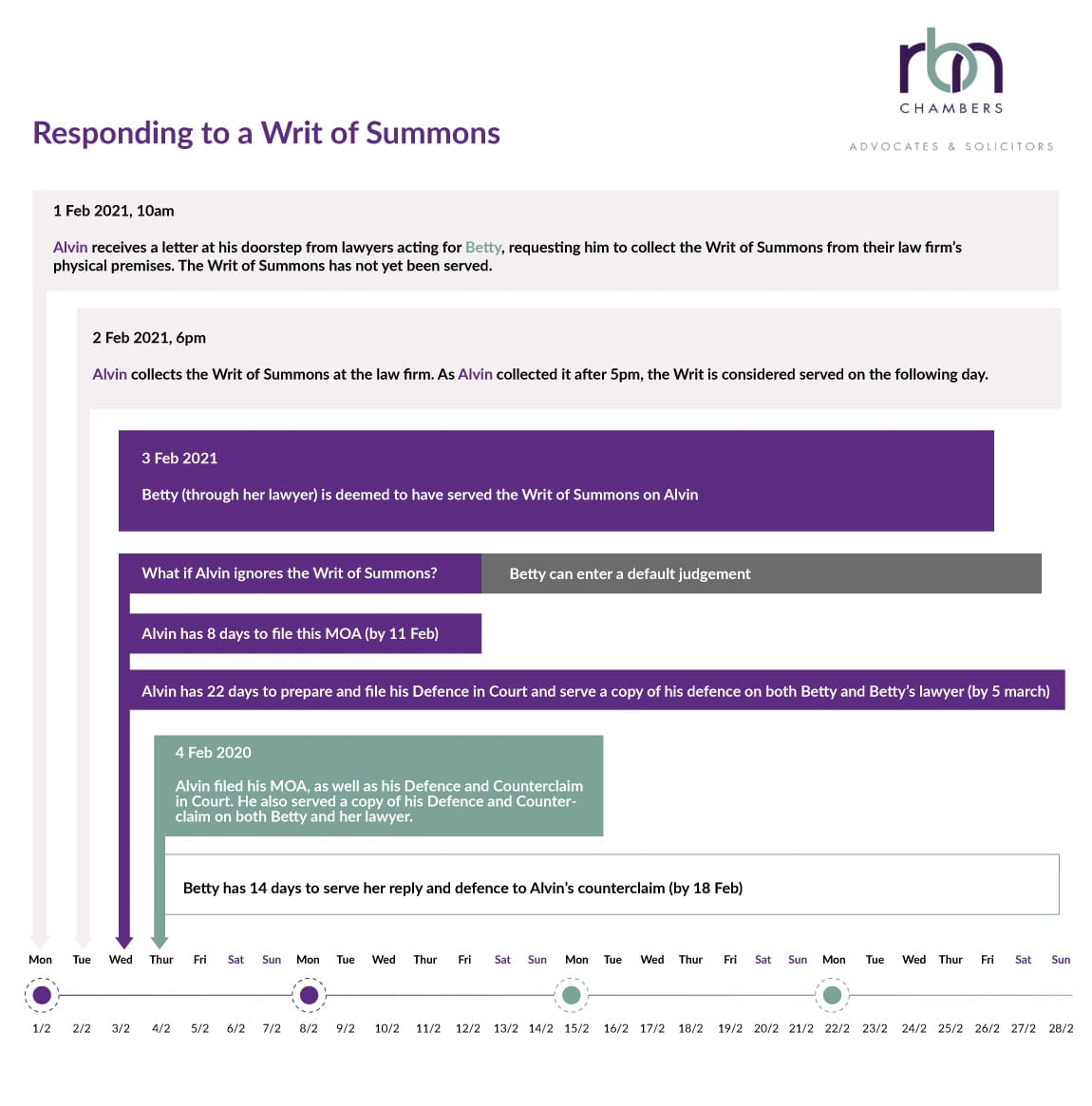

When you receive a Writ of Summons, you must decide if you wish to contest the claim as a defendant. We have summarised the process after receiving the Writ of Summons into a diagram to help you visualize the timeline and actions required.

There are cases where the defendant does not dispute the claim i.e. as the defendant, you acknowledge that you owe the plaintiff.

In such circumstances, you can contact the plaintiff or their lawyer to negotiate a settlement and therefore minimize legal costs without going through a trial.

Filing a Memorandum of Appearance (MOA)

Regardless of whether you are defending yourself against the claim or seeking a settlement, we would advise that you enter an appearance as soon as possible by filing a Memorandum of Appearance (MOA) in Court before the deadline stipulated on the writ.

You can simply do so online via the eLitigation website or via hardcopy format at the CrimsonLogic Service Bureau at a fee.

If you fail to file an MOA by the deadline, you may be unable to defend your case, and a judgement may be given against you by default. This may be a final judgement or an interlocutory judgement, depending on the nature of the claim.

If you are in Singapore, you will have 8 days to file the MOA upon being served the Writ of Summons. If you are abroad, you will have 21 days.

Do take note of the conventions for calculating time:

- 8 days refers to 8 normal days, rather than working days.

- Anything done after 5 pm (GMT +8) is considered as occurring on the next day.

Entering an appearance does not mean that the dispute has to end in a lawsuit.

At this point, it is recommended that you seek legal advice. A civil lawyer will be able to advise you on your available options, including whether your defence has merit or whether you can counter-sue the plaintiff.

Serving your Defence and/or Counterclaim

As a defendant, if you feel that the claim against you is unreasonable, or unfounded, you can choose to contest the claim by serving your Defence on the plaintiff.

Within 22 days from the date that you were served with the Writ of Summons, you must file your defence in Court and serve a copy of your defence on the plaintiff’s address of service or on the plaintiff’s solicitors at their office address.

If you believe that you have a claim or are entitled to any relief or remedy against the plaintiff, you may make a counterclaim in the same action brought by the plaintiff.

In such a case, the pleading is known as the defence and counterclaim.

In the event of counterclaim, the plaintiff will have to serve his/ her reply and defence within 14 days.

Should you ignore the Writ of Summons?

We would advise you not to ignore the writ as it does not eliminate the impending legal action. In fact, by doing so, the plaintiff has the option of entering a default judgment.

If the Court approves the default judgment, the defendant would be deemed to have automatically ‘lost’ the suit, somewhat similar to a forfeit, and judgment can be entered against you for the appropriate reliefs claimed by the plaintiff.

Legal Expertise for Civil Action

The legal process of litigation in Singapore is complex and requires knowledge of legal form and process.

As a plaintiff, you may lose your case before it even gets to court, and as a defendant, you may find yourself on the wrong end of a default judgment if you do not understand the rules governing civil actions.

If you are considering commencing civil action against a defendant or if you are being sued in Singapore, you should seek legal advice from a lawyer with experience in civil procedure and litigation.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a Letter of Demand?

A Letter of Demand is a document that sets out a list of demands for the recipient to comply with, often sent by a lawyer on behalf of a claimant. In most cases, it is issued before commencing legal action and serves as a final warning, giving the recipient a chance to resolve the matter within a stipulated time. If the demands are not met, the claimant may proceed to file a Writ of Summons to begin formal court proceedings. However, sending a Letter of Demand is not a legal prerequisite —claimants can choose to initiate civil action directly without making prior demands.

What is a Statement of Claim?

A Statement of Claim is a court document often issued together with a Writ of Summons. It outlines the nature of the plaintiff’s claim, the relevant facts, and the relief or compensation sought. If it is not served at the same time as the Writ, the Writ may include a brief summary of the claim, and the full Statement of Claim must then be served within 14 days after the defendant enters an appearance.

Delivering Solutions not just Answers to your legal disputes

We provide solutions to the table for all our clients regardless of the scale or complexity of the cases. Let us know how we can help.

Contact UsAny information of a legal nature in this blog is given in good faith and has been derived from resources believed to be reliable and accurate. The author of the information contained herein this blog does not give any warranty or accept any responsibility arising in any way, including by reason of negligence for any errors or omissions herein. Readers should seek independent legal advice.